How Grand He Is

FROM THE BASEBALL GEEKLY FILES:

The Grand Salami. No, not the guy that played with Gomez and Coolidge on “The White Shadow.” And not the big stick of cured meat that hangs in Satriale’s on “The Sopranos.” I’m talking about the Grand Slam, one of the most majestic events in baseball, in which a batter hits a home run with the bases loaded, driving in four runs to aid his team’s cause, while deflating the opposing team.

Grand slams are particularly exciting (and deflating) when they win a game, turning the post-game macaroni salad into risotto for the winners. Statisticians love to argue over what defines clutch hitting, looking at all sorts of averages with runners in scoring position, etc. But nothing makes Jim from Queens say, “Now dat guy’s clutch, ya know?” faster than a grand slam.

On Tuesday night, Jim had plenty to talk about, as the Mets’ Robin Ventura turned a 4-3 deficit into a 7-4 lead with one swing of the bat, en route to a 7-5 victory over the Houston Astros. It was Ventura’s 15th career grand slam, moving him into ninth place on the all-time list, and breaking a tie with the Reds’ Ken Griffey, Jr.

So, is Ventura a clutch hitter? Certainly those timely home runs would suggest that he has a knack for coming up with big hits, but do the numbers hold true? It depends on your definition of clutch hitting. Some would argue, and not without merit, that hitters who do well in the postseason are clutch, as they are producing for their teams at the most important time. In that sense, Ventura has as much in common with clutch as a car with automatic transmission. In 107 postseason at bats with both the White Sox and Mets, Ventura has 18 hits, for a .168 average. During that same span, his on base percentage (OBP) is .315 and his slugging percentage (SLG) is .299, for a composite on base plus slugging (OPS) of .614. Not only are these numbers unusually low, his SLG is actually lower than his OBP, which is quite rare, particularly for a guy who can hit for power (albeit not in the postseason).

For comparison’s sake, for his career (through Tuesday), Ventura has a career batting average of .273, an on base percentage of .365 and a slugging percentage of .450, all significant improvements over his postseason numbers. While some might choose to focus on the postseason, it is also true that a team must win a sufficient number of its regular season games even to make the postseason. In that sense, clutch hitting during the regular season is crucial.

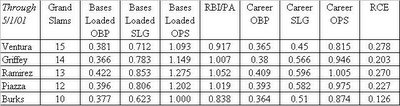

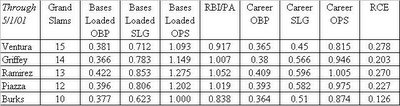

It is in this light that Ventura truly shines, particularly with the bases loaded. For his career, he is 49-for-139, or .353, with the bases loaded. As previously mentioned, 15 of those 49 hits were home runs; five were doubles, with the other 20 hits being singles. So his lifetime slugging percentage (total bases/at bats) with the bases loaded is .712. But he hasn’t just done his damage by swinging. He has also drawn 19 walks with the bases loaded and been hit once by a pitch. Now, his career on base percentage is .381 with the sacks juiced. Put those numbers together and his OPS with the bases loaded is 1.093. That’s a big number.

But if you only focused on OPS, you would be missing RBI generated by sacrifice flies. That is, with fewer than two outs, the batter hits a fly ball to the outfield that is caught for an out, but is hit deep enough for the runner on third to tag up and score. The batter has sacrificed himself for the good of the team. You see, on base percentage is calculated as follows:

(Hits + Walks + Hit By Pitch)/

(Hits + Walks + Hit By Pitch + Sacrifice Flies)

So a hitter’s OBP is actually hurt by driving in a run via the sacrifice fly, but the name of the game is scoring runs. Well, the name of the game is baseball, but I digress. In total, he has 166 RBI in 181 total plate appearances (139 at bats, plus 19 walks, plus one hit by pitch, plus 22 sacrifice flies) with the bases loaded, or .92 RBI/plate appearance.

How does Ventura compare to other active players with a penchant for grand slams? As was mentioned, he was tied with Griffey prior to Tuesday’s heroics. Griffey is a career .339 hitter with the bases loaded (39-for-115), with a .783 SLG and a .366 OPB. So his OPS is a bit higher than Ventura’s (1.149 vs. 1.093), but how about his RBI per plate appearance? He has 132 RBI in 131 plate appearances, averaging just over one RBI per plate appearance with the bases loaded. That is clutch.

But while his OPS with the bases loaded is 1.149, his career OPS in all situations is .946, so his OPS is .203 points higher with the bases loaded. Ventura, on the other hand, has a career OPS of only .815, so his 1.093 with the bases loaded is actually .278 higher with the bases loaded. So, creating a new statistic here, Ventura’s RCE (or relative clutch enhancement) is actually considerably higher than is Griffey’s. That is, relative to his usual performance, Ventura actually does better with the bases loaded than does Griffey relative to his usual performance.

We’ll just check a few more noted active grand slam sluggers, namely those with 10 or more career grannies through Tuesday. For simplicity’s sake, we’ll only use players whose careers began in 1987 or later because our statistical database at this point only carries the situations (bases loaded, two men on, etc.) back until 1987. As we can see, the three added contestants, Manny Ramirez, Mike Piazza and Ellis Burks all have higher OPS with the bases loaded (which is part of the reason they are on the grand slam list). Ramirez clearly does the most damage with the bases loaded, driving in 1.275 runs per plate appearance. But once again, Ventura is the dog who has his day, as his OPS jumps the most with the bases loaded relative to these other players in the same situation.

Ventura is already in the record books for his grand slam feats. He is the only player in history to have hit a grand slam during both games of a doubleheader. He is also the only player to have twice hit two in a day, the doubleheader with the Mets in 1999 and once with Chicago in 1995 in the same game.

Where will he wind up on the all-time list (UPDATE: He retired after the 2004 season with 18)? Well, he’s in 9th place now, but that’s a lot different than being in 9th place in other categories. For instance, entering the season, the Rangers' Andres Galarraga was in 9th place all-time in strikeouts. Through perseverance, and his insistence at swinging and missing, Galaragga has already surpassed Dale Murphy and Bobby Bonds this year, to move into 7th place with 1,768 for his career. Despite his best efforts to not make contact, he will never catch Reggie Jackson, who sits safely (for now) at the top with 2,597.

On the other hand, Ventura is 9th with his 15 grand slams, while Lou Gehrig sits at the top of the list with 23. In front of Ventura sits one of the most awesome gathering of sluggers in the game’s history: Babe Ruth, Hank Aaron and Dave Kingman at 16; Ted Williams and Jimmie Foxx at 17; Willie McCovey at 18; Eddie Murray at 19, and Gehrig at 23. All are Hall of Famers except for Murray, who will be in a few years when he becomes eligible, and Kingman, who has the most home runs (442) of anybody eligible, but not yet elected, to the Hall (soon to be surpassed by Jose Canseco, who will someday be eligible, but won’t make it). In addition, Ventura’s grand slams are a much higher percentage of his total home runs (6.5%) than those ahead of him, with Gehrig next at 4.7%. At his current pace of one grand slam per 378 at bats, Ventura would need another 6-plus years of 500 at bats to catch Gehrig. Given his recent health issues, that’s an iffy proposition. But as we’ve seen, Ventura tends to perform much better under pressure.

The Grand Salami. No, not the guy that played with Gomez and Coolidge on “The White Shadow.” And not the big stick of cured meat that hangs in Satriale’s on “The Sopranos.” I’m talking about the Grand Slam, one of the most majestic events in baseball, in which a batter hits a home run with the bases loaded, driving in four runs to aid his team’s cause, while deflating the opposing team.

Grand slams are particularly exciting (and deflating) when they win a game, turning the post-game macaroni salad into risotto for the winners. Statisticians love to argue over what defines clutch hitting, looking at all sorts of averages with runners in scoring position, etc. But nothing makes Jim from Queens say, “Now dat guy’s clutch, ya know?” faster than a grand slam.

On Tuesday night, Jim had plenty to talk about, as the Mets’ Robin Ventura turned a 4-3 deficit into a 7-4 lead with one swing of the bat, en route to a 7-5 victory over the Houston Astros. It was Ventura’s 15th career grand slam, moving him into ninth place on the all-time list, and breaking a tie with the Reds’ Ken Griffey, Jr.

So, is Ventura a clutch hitter? Certainly those timely home runs would suggest that he has a knack for coming up with big hits, but do the numbers hold true? It depends on your definition of clutch hitting. Some would argue, and not without merit, that hitters who do well in the postseason are clutch, as they are producing for their teams at the most important time. In that sense, Ventura has as much in common with clutch as a car with automatic transmission. In 107 postseason at bats with both the White Sox and Mets, Ventura has 18 hits, for a .168 average. During that same span, his on base percentage (OBP) is .315 and his slugging percentage (SLG) is .299, for a composite on base plus slugging (OPS) of .614. Not only are these numbers unusually low, his SLG is actually lower than his OBP, which is quite rare, particularly for a guy who can hit for power (albeit not in the postseason).

For comparison’s sake, for his career (through Tuesday), Ventura has a career batting average of .273, an on base percentage of .365 and a slugging percentage of .450, all significant improvements over his postseason numbers. While some might choose to focus on the postseason, it is also true that a team must win a sufficient number of its regular season games even to make the postseason. In that sense, clutch hitting during the regular season is crucial.

It is in this light that Ventura truly shines, particularly with the bases loaded. For his career, he is 49-for-139, or .353, with the bases loaded. As previously mentioned, 15 of those 49 hits were home runs; five were doubles, with the other 20 hits being singles. So his lifetime slugging percentage (total bases/at bats) with the bases loaded is .712. But he hasn’t just done his damage by swinging. He has also drawn 19 walks with the bases loaded and been hit once by a pitch. Now, his career on base percentage is .381 with the sacks juiced. Put those numbers together and his OPS with the bases loaded is 1.093. That’s a big number.

But if you only focused on OPS, you would be missing RBI generated by sacrifice flies. That is, with fewer than two outs, the batter hits a fly ball to the outfield that is caught for an out, but is hit deep enough for the runner on third to tag up and score. The batter has sacrificed himself for the good of the team. You see, on base percentage is calculated as follows:

(Hits + Walks + Hit By Pitch)/

(Hits + Walks + Hit By Pitch + Sacrifice Flies)

So a hitter’s OBP is actually hurt by driving in a run via the sacrifice fly, but the name of the game is scoring runs. Well, the name of the game is baseball, but I digress. In total, he has 166 RBI in 181 total plate appearances (139 at bats, plus 19 walks, plus one hit by pitch, plus 22 sacrifice flies) with the bases loaded, or .92 RBI/plate appearance.

How does Ventura compare to other active players with a penchant for grand slams? As was mentioned, he was tied with Griffey prior to Tuesday’s heroics. Griffey is a career .339 hitter with the bases loaded (39-for-115), with a .783 SLG and a .366 OPB. So his OPS is a bit higher than Ventura’s (1.149 vs. 1.093), but how about his RBI per plate appearance? He has 132 RBI in 131 plate appearances, averaging just over one RBI per plate appearance with the bases loaded. That is clutch.

But while his OPS with the bases loaded is 1.149, his career OPS in all situations is .946, so his OPS is .203 points higher with the bases loaded. Ventura, on the other hand, has a career OPS of only .815, so his 1.093 with the bases loaded is actually .278 higher with the bases loaded. So, creating a new statistic here, Ventura’s RCE (or relative clutch enhancement) is actually considerably higher than is Griffey’s. That is, relative to his usual performance, Ventura actually does better with the bases loaded than does Griffey relative to his usual performance.

We’ll just check a few more noted active grand slam sluggers, namely those with 10 or more career grannies through Tuesday. For simplicity’s sake, we’ll only use players whose careers began in 1987 or later because our statistical database at this point only carries the situations (bases loaded, two men on, etc.) back until 1987. As we can see, the three added contestants, Manny Ramirez, Mike Piazza and Ellis Burks all have higher OPS with the bases loaded (which is part of the reason they are on the grand slam list). Ramirez clearly does the most damage with the bases loaded, driving in 1.275 runs per plate appearance. But once again, Ventura is the dog who has his day, as his OPS jumps the most with the bases loaded relative to these other players in the same situation.

Ventura is already in the record books for his grand slam feats. He is the only player in history to have hit a grand slam during both games of a doubleheader. He is also the only player to have twice hit two in a day, the doubleheader with the Mets in 1999 and once with Chicago in 1995 in the same game.

Where will he wind up on the all-time list (UPDATE: He retired after the 2004 season with 18)? Well, he’s in 9th place now, but that’s a lot different than being in 9th place in other categories. For instance, entering the season, the Rangers' Andres Galarraga was in 9th place all-time in strikeouts. Through perseverance, and his insistence at swinging and missing, Galaragga has already surpassed Dale Murphy and Bobby Bonds this year, to move into 7th place with 1,768 for his career. Despite his best efforts to not make contact, he will never catch Reggie Jackson, who sits safely (for now) at the top with 2,597.

On the other hand, Ventura is 9th with his 15 grand slams, while Lou Gehrig sits at the top of the list with 23. In front of Ventura sits one of the most awesome gathering of sluggers in the game’s history: Babe Ruth, Hank Aaron and Dave Kingman at 16; Ted Williams and Jimmie Foxx at 17; Willie McCovey at 18; Eddie Murray at 19, and Gehrig at 23. All are Hall of Famers except for Murray, who will be in a few years when he becomes eligible, and Kingman, who has the most home runs (442) of anybody eligible, but not yet elected, to the Hall (soon to be surpassed by Jose Canseco, who will someday be eligible, but won’t make it). In addition, Ventura’s grand slams are a much higher percentage of his total home runs (6.5%) than those ahead of him, with Gehrig next at 4.7%. At his current pace of one grand slam per 378 at bats, Ventura would need another 6-plus years of 500 at bats to catch Gehrig. Given his recent health issues, that’s an iffy proposition. But as we’ve seen, Ventura tends to perform much better under pressure.