Teddy Ballgame, Part One: 1941

FROM THE BASEBALL GEEKLY FILES:

In our last column, we served up a take on the popular barroom debate topic: what makes someone a Most Valuable Player in Major League Baseball? As we learned, since the inception of the present form of the award in 1931, the MVP in each league has played for a playoff-bound team roughly 70% of the time. We saw that pure offensive dominance is not always enough, as we examined the cases of the Phillies' Chuck Klein in 1933 and the Yankees' Lou Gehrig in 1934, two players who won the Triple Crown Award by leading their leagues in batting average, home runs and runs batted in, but did not win the MVP award.

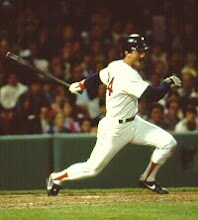

Think that's unlucky? At the intersection of baseball and unlucky is an institution known as the Boston Red Sox, whose most famous inmate was Ted Williams. The Red Sox' Ted Williams holds the dubious distinction of twice winning the Triple Crown and losing the MVP race in the same season. Today we begin the first of our four-part series on Williams, primarily focusing on the 1941 season of magic.

The 1940s were a golden decade for Williams, a native of San Diego. After his stellar rookie season in 1939, in which Williams hit .327, with 31 home runs and 145 RBI (the greatest rookie season ever?), he stormed into the 40s, racking up as many hitting accolades as nicknames. Named "The Kid" for his youthful exuberance, he applied all of his energy towards becoming a better hitter; his critics maintained that he and the Red Sox might have been better served if he had applied some of that energy to becoming a better outfielder.

Though Williams' home runs and RBI dropped off a little in 1940, he began to show increasing discipline at the plate, striking out less and improving his average to .344 (his career average, by the way). That season also featured the only pitching performance of The Kid's career. On August 24th, Williams pitched the final two innings of what would be a 12-1 loss to the Detroit Tigers, giving up one run on three hits, and striking out Tigers' first baseman Rudy York, who was in the midst of his best season. In a sweet bit of baseball symmetry, Williams' catcher that day was Joe Glenn, the same catcher who caught Babe Ruth's last pitched game, a complete game victory in 1933 for the Yankees.

The next season, 1941, would come to define Williams. With his scientific approach to hitting and his sweet swing, "The Splendid Splinter" launched an assault on American League pitching. After a May 2nd game against at Cleveland, Williams' average reached its lowest point of the season, at .308. After an 0-for-5 performance against Chicago on May 14th at Fenway Park, Williams was at .336. The next day, May 15th, began one of the most exciting periods of individual achievement in baseball history. Like the Yankees' Mickey Mantle and Roger Maris in 1961 (or for those of you under the influence of the Recency Effect, like the Cardinals' Mark McGwire and the Cubs' Sammy Sosa in 1998), Williams was not alone in his pursuit of excellence that summer.

After an early season slump, the Yankees' Joe DiMaggio, the two time defending batting champion, went 1-for-4 on May 15th with a scratch single off his bat handle. He did not stop hitting safely for over two months. Though DiMaggio captured more attention during the early part of that summer, Williams was certainly not just an also-ran. Between May 15th and June 7th, DiMaggio hit safely in 22 consecutive games. During that same period, Williams hit safely in 23 consecutive games, to lift his average to .431 (he had been as high as .436 through June 6th).

With the help of several favorable scoring decisions, DiMaggio kept the streak going into July. On July 2nd, against the Red Sox, DiMaggio hit a home run, running his consecutive games streak with a hit to 45, breaking Wee Willie Keeler's 1897 record of 44. DiMaggio broke the record using teammate Tommy Henrich's bat, as someone had stolen DiMaggio's favorite bat the day before during a rain delay. His record-breaking home run off Boston's Dick Newsome flew over the head of Ted Williams as it traveled into the left field stands. By the end of that game, Williams' average was at .401.

Going into the All-Star break, Williams was at .405 and DiMaggio's streak had grown to 48 games, through July 6th. The All-Star Game belonged to Williams. On July 8th in Detroit's Briggs Stadium, Williams came to bat in the bottom of the ninth against the Cubs' Claude Passeau. The score was 5-4 in favor of the National League, there were two out and two men on base. Williams won the game, 7-5, with one of the most dramatic hits of his career, a home run to the upper deck in right field. DiMaggio did double in the game, though it did not count towards the streak, as it was not a regulation game.

After the break, the attention quickly shifted back to DiMaggio. He kept hitting for eight more games, before the Cleveland Indians shut him down on July 17th, thanks mostly to the great defense of third baseman Ken Keltner and shortstop Lou Boudreau. DiMaggio's streak of 56 consecutive games with a hit stands to this day, and will likely never be broken; the closest anyone has come was Cincinnati's Pete Rose, whose streak hit 44 games in 1978.

During the streak, DiMaggio hit .408, with 56 singles, 56 runs scored and 55 RBI. Overall, he had 91 hits during the period, 15 of which were home runs. It should be noted, that in 34 of the 56 games, he had only one hit, thus truly relying on a combination of luck, generous calls and pure determination to keep the streak alive. After it ended, he then hit safely in 16 straight games, or 72 out of 73 games. This streak, too, will likely never be broken.

While DiMaggio continued his road to immortality after the All-Star break, Williams temporarily stumbled off the path. He went 0-for-5 in his first two games back, and then missed six of the next seven games due primarily to an ankle injury. After some limited play for three games, which included a pinch-hit home run, he missed another game. Entering play on July 22nd, Williams was at .396. The time off proved invaluable, as Williams resumed the race for .400. By the end of July he was up to .409 and by the end of August he was at .407. He had one more month to become the first player since the Giants' Bill Terry in 1930 to hit .400 for a season (Terry hit .401).

As the Red Sox were too far back to catch the first place Yankees, Red Sox manager Joe Cronin suggested that Williams sit out on September 27th in Philadelphia in order to maintain his average, which had "fallen" to .401. Williams played on, and went 1-for-4 to lower his average to .3995. Knowing that The Kid's average would be rounded off to .400, Cronin again offered Williams the chance to sit down in the season-ending doubleheader against the A's on the 28th. Again, Williams refused to sit out and rest on his record. Williams went 6-for-8 in the two games, ending the season with a .406 average. Williams, who turned 23 on August 30th that year, became the youngest player ever to hit .400 for a season. No player has since reached that lofty plateau, but perhaps this year, on the 60th anniversary of the feat, another Red Sox player from Southern California, Nomar Garciaparra, will make a run at .400 (UPDATE: Not quite, but Nomar did hit .372 that year).

After the season, the baseball writers voted DiMaggio the league's Most Valuable Player, edging out Williams 291-254. The 26-year-old DiMaggio, who had previously won the award in 1939, was favored largely on the strength of his 56-game hitting streak and the Yankees' berth in the World Series. Was Williams snubbed? Here are their major statistics for the season:

DiMaggio R 122 HR 30 RBI 125 BA .357 OBP .440 SLG .643 OPS 1.103

Williams R 135 HR 37 RBI 120 BA .406 OBP .551 SLG .735 OPS 1.286

Looking at the first four categories, we see that Williams bested DiMaggio in runs scored, home runs and batting average, while DiMaggio drove in more runs. But take a look at the next two "less glamorous" columns. Williams far surpassed DiMaggio in On Base Percentage, a measure of a hitter's ability to reach base safely (via hit, walk or hit by pitch) and Slugging Percentage, a measure of a hitter's ability to hit for power (total bases divided by at bats). The composite measure, OPS, which takes both into account, shows that Williams blew DiMaggio away.

But sportswriters in 1941 did not look at OPS as a measure of production, and barely do today either. But they should. What's truly amazing about Williams' OPS in 1941 is where it ranks all-time. Of the top eight OPS seasons, Babe Ruth holds spots 1-3, 5 and 7-8. Not too shabby. But Williams' 1941 season holds spot number 4 and another stellar year of his that we'll hear about later is at number 6. DiMaggio's 1941 season is good enough for 95th place on the all-time list. We might see someone with a .400 batting average again before we see someone duplicate Williams' 1.286 OPS (UPDATE: Barry Bonds has since taken hold of 4 of the top 8 spots, and Williams' 1941 season ranks 7th). The closest player since 1941 (other than Williams again) was Mark McGwire in 1998, who finished at 1.222, good for 12th place all-time. Of course, McGwire didn't win MVP that year either, losing out to Sammy Sosa and his 1.024. Why? Sosa's Cubs made the playoffs, a recurring theme.